US-Mexico Travellers Database

David McKenzie, a public historian at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, DC and PhD candidate at George Mason University in Virginia, USA, uses Heurist to assist with his research of data on people travelling between the US and Mexico between 1820 and 1846.

U.S.-Mexico Travelers and Migrants Database

In the early nineteenth century, the United States and Mexico moved simultaneously toward increasing interconnection and interdependence—and war. Thousands of U.S.-Americans migrated into Mexico. While U.S. expatriates in the northern Mexican region of Texas unintentionally laid the groundwork for a future U.S. territorial empire, those who settled further into the country’s interior laid the groundwork for another form of empire: A commercial empire that would, in fits and starts, take an increasing role in Mexico and, eventually, other parts of Latin America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The first migration is widely known. The second is not. My dissertation examines this second migration through the career of two U.S.-American brothers, John and Samuel Baldwin, who settled in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the early 1820s and remained engaged in U.S.-Mexican affairs for the next 30 years.

Why a Database?

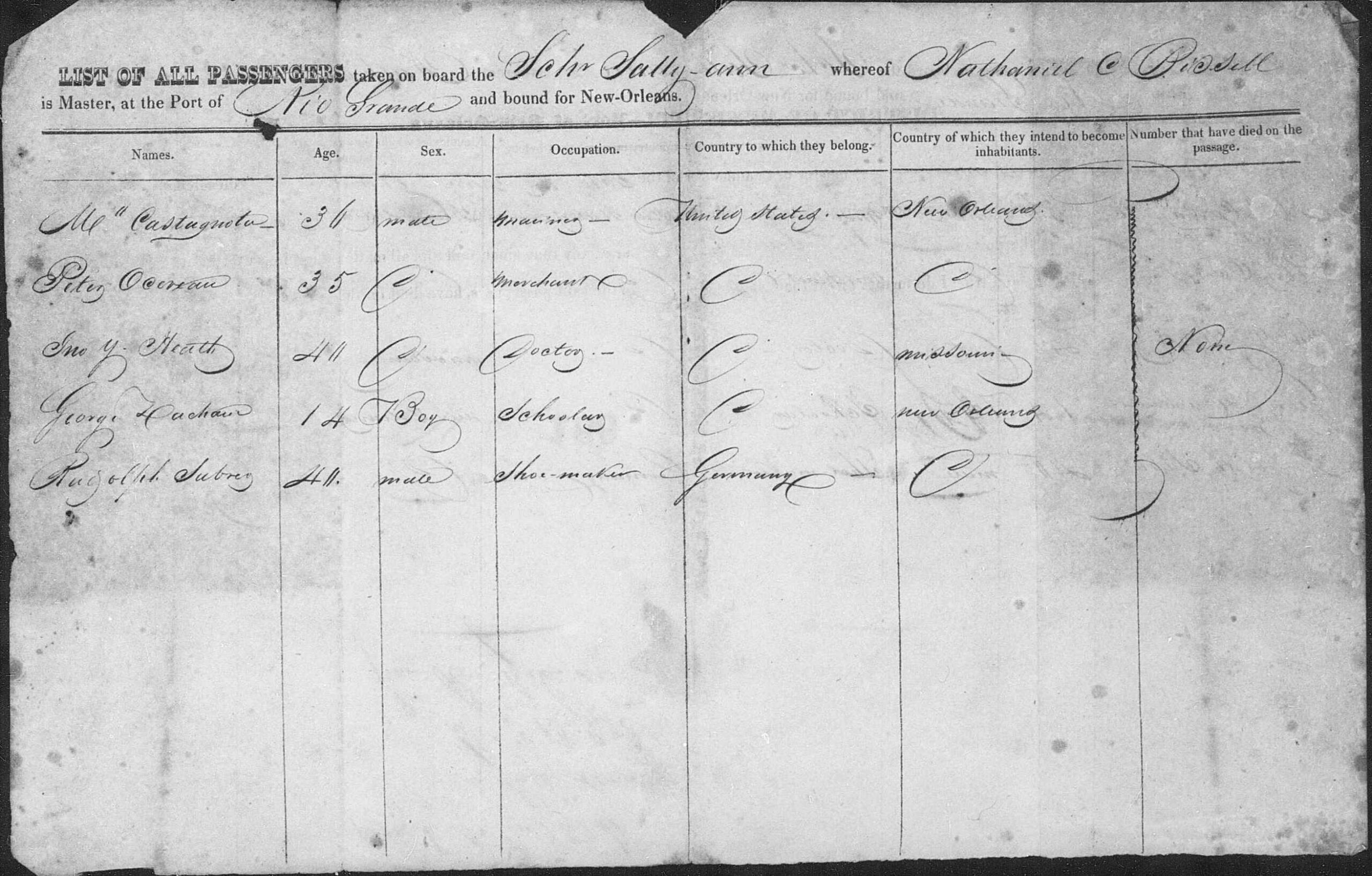

While the Baldwins make for a prime case study, examining solely their careers, or even bringing in a few other case studies, will not offer an adequate portrait of U.S. migration and commercial expansion into Mexico in this era. I’ve turned to Heurist to bring quantitative analysis into my work, to examine how the Baldwins compare with other migrants. Originally I began a Heurist database for one main purpose: to quantify movement of individuals between Mexico and the United States, drawing on passenger manifests the United States began to require for vessels inbound from foreign ports in 1820. I’ve since expanded it to encompass another data set: Information I encounter in my research about any U.S.-Americans who expatriated to the interior of Mexico. Both datasets, which will contain some of the same individuals, will allow for tracking numerical change over time of travelers and migrants, extraction of social networks, and, most importantly, painting demographic portraits of travelers and expatriates.

Structure of the Database

So far I’ve worked with the ship manifests, structuring the database for that particular dataset. With Ian Johnson’s guidance, I’ve set up four main types of records:

- Trip: This is the beginning of the database. An individual person takes a voyage on a ship. Trip records include the Person, Voyage, and further information gleaned from the manifest—information that, even for the same person, can change, like age and occupation. It also includes information about where the person intends to settle.

- Person: This record type allows for stable information about a single person, including first and last name, birth date, and country of citizenship.

- Voyage: This record type includes information about the origin and destination of a particular ship voyage, link to a record of the ship itself, and ties together the various passengers who traveled.

- Ship: While less important, this separate record allows for tracking of ships used in the U.S.-Mexico trade (presuming that many of the ships of the same name were, indeed, the same ships).

Aims of the Database

As it currently stands, I see the database of passenger manifests helping inform the bigger picture I cover in the dissertation in several ways:

- How did flows of ships and people change over time, numbers-wise, between the United States and Mexico? This database will help me to track those ebbs and flows, both in aggregate and even between particular ports, potentially leading to further patterns that would be otherwise obscured.

- How did the demographics of who traveled between the two countries change during this period?

- Who frequently traveled between the two countries?

- Who frequently traveled together between the two countries? What networks might I find that would be otherwise obscured?

- When did the people I track as case studies—particularly the Baldwins—return to the United States, and how frequently did they travel back and forth, even as they lived in Mexico?

Additionally, after advice from Dr. Johnson, I plan to add another type of person data to the database: That of U.S. expatriates who settled in Mexico. I’m still working out the changes/additions I’ll need to make for the second dataset, but will likely capture pieces of data like dates of migration to and from Mexico, where and how they turn up in records, where they settled and when, family information, and connections with other expatriates and Mexican nationals. Some questions this might help answer include:

- From and to where did U.S. expatriates move? How did this change over time? Like many immigrant groups today, did migrants from particular cities or regions settle in similar regions?

- When did expatriates arrive in and depart from Mexico? Did they visit before they moved? This might yield greater insight on migration patterns, particularly correlated to particular events.

- What occupations did U.S. expatriates to Mexico undertake? Did migrants with similar occupations cluster together? This might help yield greater insight on the roles that U.S. nationals played in Mexico’s economy.

- When did incidents for which U.S. nationals filed claims against Mexico take place? Are there particular patterns among those incidents? These patterns might correlate—or might not—to low points in the U.S.-Mexico relationship.

- How did the demographics, including age, of U.S. migrants to Mexico change over time? Who was typically moving to the country at any given time?

My dissertation examines people who didn’t leave cohesive collections of papers, but for whom scraps of evidence exist in many different places, like claims they filed against the Mexican government, U.S. consular correspondence, court cases in the United States and Mexico, brief mentions in newspapers, and Mexican immigration and vital records. Using Heurist will help me to unify these different scraps and form, hopefully, more cohesive stories of both these individuals and the wider trends that both swept over them and to which they contributed.

Much, much thanks to Ian Johnson and the entire Heurist team for creating this service for the humanities community and for helping me to get my database going and continued.